The Value of Holistic Financial Advice*

Abstract: Financial advice has historically been narrowly focused on investing decisions, thus catering to a small fraction of the population with enough wealth to care about alpha. This paper explores the potential value of broader, or holistic, financial advice that also covers savings, debt and insurance decisions, which are relevant to a much broader population. The results show that there’s tremendous value in such advice, which is potentially worth more than 2,472 bps, or an income boost of 7.5% for the typical household. More importantly, this type of advice can be especially valuable for those with lower income who historically have been underserved.

Introduction

In recent years, government regulators have taken an increasingly skeptical view of the value provided by investment advisors. This has led to several new regulations, including additional disclosures around fees, broadening the definition of a fiduciary, and strict guidelines with respect to IRA rollovers. Employers are also increasingly skeptical as fiduciaries, worried that financial advice might not be worth the cost.

This skepticism is rooted into two related beliefs: advice is not valuable enough and it’s too expensive. Yet, decades of research in behavioral economics suggest people need extensive help when it comes to financial decision making, especially given the challenges of household finance in the 21st century.1 Furthermore, digital advisors should be able to provide advice at a lower cost.

Why, then, is there so much skepticism about the cost-benefit tradeoff of financial advice?

In this paper, I will argue that narrow framing is at play. By exclusively focusing on the value of investment advice, rather than broader financial advice that covers debt management, insurance and more, we vastly underestimate the value of financial advice. Similarly, by narrowly focusing on the cost of human advisors, rather than taking the broader perspective of hybrid advice featuring digital and human advisors, we likely overestimate the potential cost.

It is obviously difficult to evaluate the full impact of financial advice. In part, this is because financial advice typically involves tradeoffs and uncertainty. For example, a parent can take her daughter for ice cream today or, alternatively, save the money in a 401(k) plan and take multiple grandkids for ice cream in the future. It is not clear which strategy is better.

To solve this problem, this paper focuses on situations with sure wins. These situations are much more common than is typically assumed, especially if one looks beyond the narrow space of investment advice. (Please don’t get me wrong – investment advice is needed and valuable, it just shouldn’t be the only type of advice.) We will focus on three situations—savings, debt and insurance—in which financial guidance can offer people an arbitrage opportunity, giving them measurable upside with no downside. These sure win situations are the equivalent of getting ice cream now and in the future.

These arbitrage opportunities are big enough to significantly impact the financial wellbeing of the typical American household. When holistic advice is evaluated, it can be worth at least $4,384 per year, 7.5% of annual income, or 541 bps assuming an average 401(k) account balance for those who need advice in multiple categories.2 (If we look at the median account balance, which is more representative of most workers, this holistic advice is worth 2,472 bps. Of course, given the skewness of the distribution, the value of advice is very sensitive to account balance.)

That said, not everyone will need advice and guidance to the same degree. For example, if you’re already debt-free, you won’t need help refinancing your loans.

However, even after factoring in the variability in the need for advice, holistic financial advice is worth at least $1,230, 2.5% of income, or 151 bps across all workers. (If using the median account balance, it is worth 693 bps.)

The benefits of holistic advice are particularly necessary and impactful for low- income households. To take one example: choosing the right insurance has a 10 times larger impact on the income of low-income households relative to higher income households. Although professional financial advice has been treated like a luxury good, reserved for households with the most wealth, lower income and underserved households could actually benefit far more from affordable and holistic financial help.

Clearly, the ROI of financial advice is extremely high. However, by using the right mix of digital and human advice, the cost of advice can be significantly reduced, further boosting the ROI. Although regulators remain concerned about the cost of financial advice, it’s the absence of holistic financial advice that turns out to be so expensive.

Sure Win 1: Retirement Savings

Research by James Choi at Yale University and David Laibson and Brigitte Madrian at Harvard University finds that nearly 40 percent of older workers are leaving “$100 bills on the sidewalk.”3 That’s because they are failing to maximize the company match in their 401(k) plan. While some younger workers might have reasons to not maximize the match—in many instances, it’s smarter to pay off your expensive debt first—workers older than 59.5 can cash out their contributions and the generous match at many companies. (Those younger than 59.5 can still benefit from the match, provided they’re patient.)

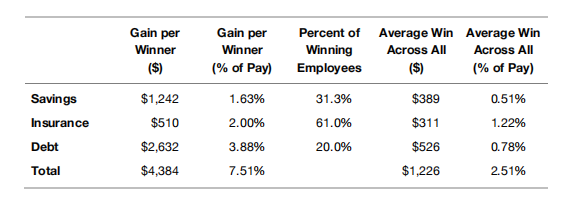

For the older workers studied by the scientists, the failure to maximize the match proved quite costly. While there is a large amount of variability across different companies in terms of average win per employee, the median company displayed an average potential win worth 1.63% of annual salary, or $1,242 per worker (see Table 1).4

TABLE 1

Of course, most employees are not in their 60s, and thus can’t immediately benefit from this sure win. However, there are additional arbitrage opportunities in the savings domain that apply to workers of all ages. Consider research by Taha Choukhmane at MIT, Lucas Goodman at the United States Treasury and Cormac O’Dea at Yale. They looked at couples who both have access to 401(k) accounts with employer matches. To optimize their benefit, couples should increase their contributions to the employer with the higher match. Unfortunately, roughly 25% of couples fail to do this, which costs them an average of $700 per year.5 These couples can surely benefit from professional financial advice. In this case, a digital advisor could help them optimize the allocation to their respective retirement savings.

Some might object that these benefits from advice are short-lived, as people will eventually learn how to maximize their match. However, it’s worth noting that those older workers had a mean tenure of 16 years, and still failed to maximize their match.

Without actionable advice, they are unlikely to ever realize the sure win.

Others might object that many people think they can manage their finances on their own. However, the available evidence suggests that the vast majority of these people are still likely to benefit from financial advice. Research I conducted with Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler showed that 80% of those who declined investment advice, and created their own portfolios, actually preferred the professional portfolios when shown the impact of their selections on retirement outcomes.

Far more advice is needed than people realize.

Sure Win 2: Debt Management

Although financial advice has typically focused on the management of assets, American households carry more than $16.5 trillion in debt, including mortgages, as of 2022.6 This amount exceeds the value of all DC retirement plans by $7.2 trillion,7 which is why holistic financial advice should also help households manage their debt.

Research by Benjamin Keys and Devin Pope at the University of Chicago and Jaren Pope at Brigham Young University found that about 20% of households with good credit fail to refinance their mortgage despite lower available rates, with the average household paying $2,632 extra per year.8 For the typical worker, that’s equivalent to roughly 3.88% of their annual income.9

Furthermore, because the mortgage is almost always the largest single expense for homeowners, effective refinance strategies can save them large sums of money, which they can invest in ways that boost their financial wellbeing. Over the lifetime of the mortgage, after factoring in complexities such as the probability of the household moving, the cost of refinance, and taxes, the researchers estimate a gain of $15,797.10

While mortgage rates have recently gone up, thus reducing the benefits of refinancing for many, homeowners on adjustable-rate mortgages might want to refinance before rates get even higher. (In 1982, rates were above 16%.11) Refinancing is especially relevant for households with adjustable-rate mortgages who have little financial buffer, and thus might be forced into foreclosure when their payments increase. I’m not saying that rates will continue to increase. Rather, I’m simply pointing out that people need ongoing advice, and that this advice should reflect their entire financial picture.

More generally, mortgage rates will continue to fluctuate over time. There will be periods where more people will benefit from refinancing, and periods when fewer will benefit. But through all the ups and downs, one constant remains: people will need holistic financial advice to ensure they aren’t wasting money on their debt.

But what if there aren’t any opportunities to refinance the mortgage, either because rates have risen, or the household doesn’t own a home? There are still likely to be savings from helping people manage their other forms of debt. Consider credit cards. Recent research by John Gathergood at the University of Nottingham and colleagues finds that households fail to prioritize repayment for credit cards with higher interest rates.12 For households with five or more credit cards, this mistake costs them, on average, $1,571 per year.13 Just imagine how else that money could be used to improve their financial wellbeing.

Sure Win 3: Insurance

Research by Saurabh Bhargava and George Loewenstein at Carnegie-Mellon University and Justin Sydnor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that 61% of workers chose the wrong health insurance plan.14 For these workers, it was a costly error, leading them to overspend by an amount equivalent to 24% of the typical premium. This is equivalent to losing $510 per year, or roughly 2% of their annual income.15 This is an especially problematic mistake given that many people now

purchase health insurance online, and rely on websites that can exacerbate these mistakes.16

Why do so many people choose the wrong plan? They are drawn to insurance options with lower deductibles, but fail to realize that the additional premium cost is disproportional. For example, in the plans studied by the researchers, employees had to pay more than $500 in additional premiums to reduce their deductible from $1,000 to $750, resulting in a potential cost-savings of just $250, or half of the increase in premiums. This means they’ll be paying more for a low-deductible plan, regardless of how much health care they consume.

Taken together, these examples of sure wins from the domains of savings, debt and insurance could add up to a 7.5% pay raise for the typical worker, giving them an additional $4,384 per year in income.

Of course, not all employees will require help across all three domains. For instance, some people might be renters, and aren’t concerned about refinancing their mortgage. As a result, it’s important to think about the fraction of people who need help and the average win across all employees. For savings, the average win for all is 0.51% of salary. For debt refinancing, the average win is slightly larger at 0.78% of salary, while improving insurance selections lead to an average win of 1.22% of salary. Interestingly, this suggests that often overlooked elements of holistic financial advice— debt and insurance—generate more value than the retirement savings interventions that are more reflective of traditional financial advice. In total, these wins generate the equivalent of a 2.51% salary increase across all employees. Who wouldn’t want to give their workers a free pay raise?

One important caveat is that there’s very little data on holistic financial planning, as it has yet to be widely implemented. As a result, we are forced to add numbers from different studies that use different populations with different income levels. Although these are difficult numbers to aggregate, we expect the total projected value of advice to become more precise as more data and research become available.

If none of these sure wins are relevant for a given worker, does that mean he or she should skip financial advice? Not at all. These are just three easily measured examples of sure win situations. There are many more, including entire categories I have not addressed, such as taxes. Consider a study of the earned income tax credit (EITC) by Saurabh Bhargava at Carnegie-Mellon and Dayanand Manoli at the University of Texas, Austin.17 Approximately, 25% of eligible households fail to claim the credit18, leading to an average foregone gain of $1,681.19 That’s equivalent to more than a month of salary for these households.

Another category involves the intersection of health and wealth. Take, for instance, a common health care choice faced by millions of Americans: should they try to save money by buying generic drugs? Given the high cost of prescribed medicines,

roughly 30% of Americans either skip doses, take an over-the-counter treatment instead, or fail to fill a prescription.20 While generic drugs might seem beyond the scope of financial advice, and beyond the expertise of financial advisors, new technologies can help advisors offer guidance on a far wider range of financial decisions. For example, here’s what ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence chatbot, offered in response to my own question about generic drugs:

“Generic drugs are typically much less expensive than their brand-name counterparts. According to the FDA, generic drugs are typically 80-85% cheaper than the brand-name version. This means that if you’re currently taking a brand- name medication that has a generic version available, switching to the generic version could potentially save you hundreds or even thousands of dollars over time. It’s always a good idea to talk to your doctor or pharmacist before switching to a generic medication.”

By encouraging people to learn more about generic drugs, AI chatbots can help them “win” back 80 percent of the cost of their medications. That, in turn, can help them take their medicine as prescribed, which is likely to improve their health. More generally, it’s important for advisors to incorporate new technologies and tools that let them create wins for clients in categories that have little to do with their investment portfolios but can put money in their pockets and boost their overall wellbeing.

Probable Wins

In addition to the sure wins, there are highly probable wins that are not guaranteed, yet they could still add large amounts of value. For example, younger workers are likely to benefit from a more aggressive investment portfolio. However, myopic loss aversion leads many people to overreact to short-term market losses, and thus seek out conservative investments that are inconsistent with their extended time horizons.21 Financial advice can help clients realize the likely wins that come from buying and holding long-term investments, even though the returns are not guaranteed.

In many cases, these probable (but not sure) wins offer the biggest upside.

Consider research on the Social Security claiming decisions of American workers by David Altig at the Federal Reserve, and Laurence Kotlikoff and Victor Yifan Ye at Boston University.22 They find that virtually all Americans should delay claiming until age 65, and 90% should delay claiming until age 70. Unfortunately, only 10% of people actually do so. For workers who claim too early, the median loss is $182,370. This mistake is particularly costly for lower-income workers: their median loss is nearly 16% of retirement income, with one in four losing more than 27% of retirement income. (Of

course, not all workers have sufficient savings to delay claiming until age 70. However, every month of delay they can afford will still lead to an increase in their lifetime benefits.) While these wins aren’t certain—you might be one of the unlucky retirees who dies at a younger age—we shouldn’t discount that $182,000 gain to $0 just because there’s a chance the strategy won’t always work.

Soft Wins

Holistic advice can also feature soft wins that are not quantifiable but still provide value. One important example involves giving clients peace of mind. Seventy three percent of Americans say that their finances are their leading source of stress.23 This stress can have serious consequences, negatively impacting job performance and health outcomes. Studies show that financial stress can even increase the risk of car accidents.24 However, by reinventing financial advice for the 21st century, we can help alleviate at least some of this anxiety.

Take decumulation. The number one concern of workers entering retirement is running out of money. Thus, advice on how to create a sustainable, lifelong paycheck in retirement is surely useful, especially if it is personalized to the needs and preferences of the client. In a recent pilot I ran, offering employees approaching retirement financial guidance using the PensionPlus™ software, 78% of users reported increased peace of mind with the remaining 22% saying it “somewhat” increased their peace of mind. While this newfound peace of mind is difficult to calculate, it arguably provides tremendous value to retirees.

Not All Wins Are Created Equal

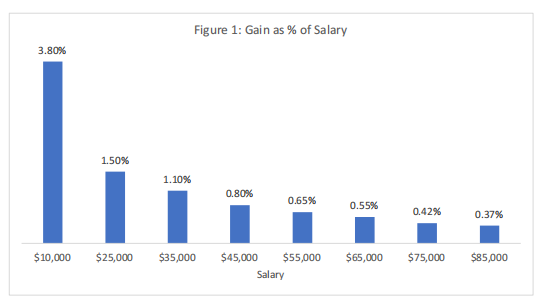

These wins are particularly impactful for low-income households. Consider health insurance. While approximately 30% of workers with annual incomes above

$100,000 chose the wrong health insurance plan, nearly 70% of workers making less than $35,000 chose the wrong plan.25 As you can see in Figure 1, they also see a much larger benefit from improved insurance selection—workers with the lowest income benefit five to ten times more, as measured by gains as a percentage of salary, than workers with higher incomes.

The best way to get sure wins for everyone, including low-income households, is to eliminate those options that are sure losers. In the case of health insurance, the advice might actually be implemented by the employer, as they should consider eliminating suboptimal plans that offer low deductibles with disproportionately high premiums.

However, making it easy to avoid losers by simply removing them from the consideration set is not always possible. Consider, for example, financial aid for low- income households. The challenge here is not the existence of losers—it’s the difficulty of winning, which requires extensive paperwork during the application process. But the general principle of “make it easy” is still critical.

Eric Bettinger at Stanford, Bridget Terry Long at Harvard and Philip Oreopoulos at the University of Toronto, showed that auto-filling the FAFSA financial aid application using existing tax records increased college enrollment rates among low to moderate income students by approximately 25 percent.26 Automatically completing financial forms is likely to also boost earned income tax credit applications, refinance applications and other wins that requires time-consuming paperwork.

Although traditional financial advice has focused on improving the investment portfolios of those who have already accumulated significant wealth, holistic guidance combined with a “make it easy” approach can greatly expand the pool of underserved households who could meaningfully benefit from advice. In some cases, it can even make it possible for students to attend college. For those who are concerned that the

impact of advice is short-lived, it’s important to remember those situations in which the advice is actually life-changing.

Evaluating Wins

Whether you’re a policy maker, fiduciary or employer, it’s important that you consider the costs and benefits of financial advice. Here are several questions to guide your evaluation process.

-

Is the advice holistic or narrow? If the advice is narrow, and is focused primarily on investments and maximizing alpha, the advice is unlikely to be valuable for those who don’t have enough wealth to care about alpha in the first place. Similarly, if the advice is provided by a marketplace of apps, each of which is focused on a specific financial domain (savings, debt, insurance, etc.) people are likely to miss the full benefits of holistic advice. For example, a savings app that doesn’t have access to information about debt costs is likely to offer misleading guidance. In order to deliver holistic advice, we need a holistic app, capable of aggregating and analyzing the relevant financial data.

-

Do the advice providers have enough data to make the advice meaningful? Retirement plan fiduciaries often debate the merits of target date funds (TDF) vs managed account solutions. TDFs are investment solutions based primarily on age. Managed accounts are a retirement plan robo-advice solution, which consider a small number of additional datapoints such as account balance and income when making investment decisions. While richer and more holistic data sets can lead to better advice, it might not be worth paying significantly more money for small data enhancements, and thus it is critical to question the marginal benefit of managed account solutions.

-

Is the advice actionable? Financial education and wellness programs aspire to provide holistic guidance, but research shows that these programs only work when their advice is actionable. This is particularly true for low-income households, who tend to benefit the least from traditional financial literacy and education programs. According to one meta-analysis by Daniel Fernandes at Erasmus University, John Lynch at the University of Colorado-Boulder and Richard Netemeyer at the University of Virginia, interventions to improve financial literacy are far less effective on low-income households compared to the overall population. 27

-

Does the advice help those who need it the most? A lot of financial advice has been focused on how workers invest their 401(k) savings. This is important, as people certainly need investment guidance. Nevertheless, the reality is that lower income individuals have more inflation-protected retirement guarantees due to their Social Security benefits. (Social Security is a progressive system, with lower income individuals getting a higher income replacement ratio.) This means that lower income workers need more help with everything else—from debt management to insurance choices—which is precisely the sort of advice they are not getting now.

-

Are the advice providers leveraging technology to reduce costs and maximize the ROI for workers? While robo-advice offers significant potential, it should lead to dramatic cost reductions. Paying 60bps for an algorithm to mix together a few ETFs raises important cost-benefit questions, at least relative to human advisors who often charge 75 to 100bps but might offer more services. In addition, employers, especially large ones, are well-positioned to offer cost- effective financial advice as an employee benefit. This is an easy way to facilitate scale and reduce costs. Given that roughly a third of Americans trust financial institutions, using employers as a bridge can also encourage people to try out the benefits of holistic advice.28

Summary

This paper contains three key takeaways about the potential value of holistic financial advice in the 21st century. The first takeaway is that the value of holistic advice is extraordinary. When advice fully reflects the financial needs and complexities of the average employee, and not just those fortunate enough to worry about the alpha of their investment portfolio, it can be worth at least $4,384 per year or 7.5% of annual income.

The second takeaway is that the value of advice is potentially up to 10 times larger for underserved groups, such as low-income households. These people are currently getting the least guidance. But they are likely to benefit the most.

The third takeaway is that many wins, especially among the underserved, can have an impact that goes way beyond dollars and cents. For those who can now afford to start taking their medications as prescribed because they are using generic drugs, and for those who will start going to college because the financial aid was easy to apply for, the potential benefits of holistic advice are life-changing. The extra income is just the icing on the cake.

Regulators are currently focused on the cost of financial advice, but the potential value of holistic advice suggests that the real problem is the lack of financial

guidance, especially among the underserved. Since only 14.4 million households have more than $500,000 in investable assets, and are thus of potential interest to human advisors, the remaining 110 million households are not getting any advice at all, let alone holistic advice.29 That is proving to be an extremely costly financial mistake.

Notes

1 Thaler, Richard H., and Shlomo Benartzi. "Save more tomorrow™: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving." Journal of Political Economy 112.S1 (2004): S164-S187.

Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard Thaler. "Heuristics and biases in retirement savings behavior." Journal of Economic Perspectives 21.3 (2007): 81-104.

Benartzi, Shlomo. Save More Tomorrow: Practical behavioral finance solutions to improve 401(k) plans. Penguin, 2012.

Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard H. Thaler. "Behavioral economics and the retirement savings crisis." Science 339.6124 (2013): 1152-1153.

2 Account balance information is based on ICI Research/EBRI, “Changes in 401(k) account balances 2010-2019,” June 2022, Vol 28.

3 Choi, James J., David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian. "$100 bills on the sidewalk: Suboptimal investment in 401 (k) plans." Review of Economics and Statistics 93.3 (2011): 748-763.

4 All numbers in 2022 dollars using inflationtool.com. Original numbers were $677 in losses in 1998 dollars.

5 Choukhmane, Taha, Lucas Goodman, and Cormac O'Dea. "Efficiency in Household Decision-Making: Evidence from the Retirement Savings of US Couples." 114th Annual Conference on Taxation. NTA, 2021.

6 https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc

7 https://www.ici.org/statistical-report/ret_22_q3

8 Keys, Benjamin J., Devin G. Pope, and Jaren C. Pope. "Failure to refinance." Journal of Financial Economics 122.3 (2016): 482-499.

9 All numbers adjusted for inflation; original numbers were $1,920 annual loss in 2010 dollars. Average salary loss was based on real median household income of $49,445 in 2010 dollars.

https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/income_wealth/cb11- 1….

10 All numbers adjusted for inflation; original gain was $11,500 in 2010 dollars.

11 https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MORTGAGE30US

12 Gathergood, John, Neale Mahoney, Neil Stewart, and Jörg Weber. "How do individuals repay their debt? The balance-matching heuristic." American Economic Review 109.3 (2019): 844-75.

13 926£ in 2013, converted at an exchange rate of 1.32 and adjusted for inflation using inflationtool.com.

14 Bhargava, Saurabh, George Loewenstein, and Justin Sydnor. "Choose to lose: Health plan choices from a menu with dominated option." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132.3 (2017): 1319-1372.

15 Adjusted for inflation based on original cost of $373 in 2010 dollars.

16 Bhargava, Saurabh, George Loewenstein, and Shlomo Benartzi. "The costs of poor health (plan choices) & prescriptions for reform." Behavioral Science & Policy 3.1 (2017): 1-12.

17 Bhargava, Saurabh, and Dayanand Manoli. "Psychological frictions and the incomplete take-up of social benefits: Evidence from an IRS field experiment." American Economic Review 105.11 (2015): 3489-3529.

18 Plueger, Dean. “Earned Income Tax Credit Participation Rate for Tax Year 2005.” Internal Revenue Service Research Bulletin, 2009. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/09resconeitcpart.pdf

19 Adjusted for inflation using inflationtool.com. Original amount from 2005 was $1,096.

20 Hamel, Liz, Lunna Lopes, Ashley Kirzinger, Grace Sparks, Audrey Kearney, M. Stokes, and Mollyann Brodie. “Public Opinion of Prescription Drugs and their Prices,” Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF.org) October 20, 2022.

21 Benartzi, Shlomo, and Richard H. Thaler. "Myopic loss aversion and the equity premium puzzle." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110.1 (1995): 73-92.

22 Altig, David, Laurence J. Kotlikoff, and Victor Yifan Ye. How Much Lifetime Social Security Benefits Are Americans Leaving on the Table?. No. w30675. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

23 https://www.capitalone.com/about/newsroom/survey-reveals-tension-betwee…

24 Meuris, Jirs, and Carrie Leana. "The price of financial precarity: Organizational costs of employees’ financial concerns." Organization Science 29.3 (2018): 398-417.

French, Declan, and Donal McKillop. "The impact of debt and financial stress on health in Northern Irish households." Journal of European Social Policy 27.5 (2017): 458-473.

25 Bhargava, Saurabh, George Loewenstein, and Justin Sydor. "Choose to lose: Health plan choices from a menu with dominated option." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132.3 (2017): 1319-1372.

26 Bettinger, Eric, Bridget Terry Long, Philip Oreopoulos, and Lisa Sanbonmatsu "The role of application assistance and information in college decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment." The Quarterly Journal of Economics127.3 (2012): 1205-1242.

27 Fernandes, Daniel, John G. Lynch Jr, and Richard G. Netemeyer. "Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors." Management Science 60.8 (2014): 1861-1883.

28 Chicago Booth/Kellogg School Financial Trust Index 2021, http://www.financialtrustindex.org

29 LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute Analysis, 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances.