CENIE recently reflected on senior talent and the risk of losing it as a result of the ageism that dominates the workplace. Ageism in the workplace would be shaped by prejudices and stereotyped beliefs towards older workers. In fact, it is older (and not so older) women who suffer the most discrimination in employment, so much so that, once they reach 45 years of age, unemployment in women is considered risky because it is very difficult to return to the labour market. As a measure, different economic measures have emerged to alleviate the economic vulnerability generated by this situation, but the basic problem remains unresolved.

Age discrimination is based on the idea that people work better or worse depending on how old they are. It happens when we are young, because it is assumed that we have no experience and do not know how to do the job with the necessary ease. Or directly that we are a little useless, wow. It happens when we are older, because after a certain age it is assumed that we are less effective and that we work less. That we are useless again, wow. Among the elderly, discrimination at work is also accompanied by other stereotyped beliefs, such as that beyond a certain age we are not capable of adapting to new technologies. We have already seen that this is not necessarily true.

This ageism produces a great loss on the potential production of the companies and on their good functioning. Contaminated by these misconceptions a company may be losing valuable assets, with great experience, by not hiring people of a certain age. Another issue that makes ageism the big problem is that it happens when this ageism degenerates into dismissal. In addition, here an added problem is the weight that the dismissal of these people has on the public coffers. On the one hand, serious doubts are raised about the sustainability of the pension system, thus justifying the delay of retirement, but on the other, such ageist and unreasonable practices are permitted for the sustainability of the public coffers, such as the forced early retirement of people who are barely over 50 or 55 years of age and who have a great deal to contribute.

We might think that the bigger the company, the more resources it has, and therefore better devices to prevent ageism and discrimination in the workplace, whatever its manifestation. Well, no: according to a report, 71% of Ibex 35 companies pay little or no attention to employees over the age of 50. But they are also the protagonists of obligatory early retirements.

This undoubtedly contradicts the regulations of the European Union (EU), which has legal protection against age discrimination. In fact, since 2000 it has had a directive that prohibits, among other things, age discrimination in employment and occupation. These would protect all forms of unfair treatment based on age, such as more direct harassment and mobbing or more indirect forms, such as when we are not promoted because we are considered too old (or too young). The problem, as we imagine, is to be able to demonstrate that this happens (and have the energy to do so) but the legislation exists. In 2008, the European Commission proposed a new directive on the subject, promoting equal treatment irrespective of age (among other grounds of discrimination) which would prohibit discrimination in the areas of social protection, education and access to goods and services. As palace things go slowly, and European Union things more so, the proposal is being discussed by the EU Member States in the Council of the European Union.

This issue has many edges to deal with, but I wanted to focus today on a simpler question related to the previous one: do older people still work in other EU countries or do they stop working at the age of 65? According to the European Statistical Office, EUROSTAT - which is the statistical office of the European Commission, and which produces data on the European Union - in the EU, 9.5% of people aged 65 to 74 work. Rates vary greatly between countries, probably in direct relation to the ability of each country's welfare state system to meet needs in old age.

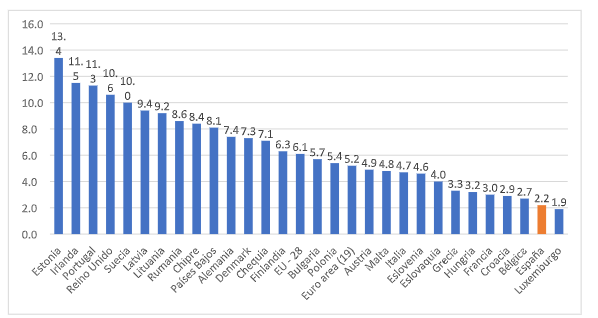

In the following graph we can see the percentage of people over 65 who work in the 28 countries of the European Union, as well as in the euro area as a whole - the United Kingdom for this time we continue to join in the post, but EUROSTAT is already ceasing to include it in the new statistics.

Chart: Employment rates (%) over 65. European Union countries, 2018.

Source: own elaboration with Eurostat data.

The range of older workers ranges from 13.4% among Estonians to 1.9% among Luxembourgers. Spain occupies the penultimate place in the ranking, with 2.2% of people over 65 who continue to form part of the labour market. In our country, Law 27 of 2011 on Pension Reform extended the retirement age to 67. This regulation established the gradual delay of retirement from 2013 at a rate of one month each year during the first six years of its application. In 2018, the last available date and the one reflected in the graph, those who had contributed more than 36 years and 9 months could still retire at 65 years of age and with 100% of the public pension. Since January 2019, the legal retirement age for receiving 100% of the public pension has increased to 65 years and eight months, so these effects cannot yet be seen in the statistics.

In other European countries, such as Iceland, the percentage of people working beyond the age of 65 is as high as 37.5%. Farther away (especially when it comes to the concept of the welfare state) in countries such as the United States, 1 in 4 over the age of 65 continues to work. Far from being the result of lower ageism in the labour market, what these data show among Americans is the lack of protection for older people. But we'll talk about that in the next post.