The ageing of the population poses major challenges to the welfare states, but at the same time offers different opportunities. In a previous entry, some notions were explained about care systems, the elements that make them up - families, the public sector, the private sector and the non-profit sector. The organization and distribution of care among these elements in a given society could be a reflection of the level of development of the care system. For example, a care system in which all care falls within the family -almost always to women- would be, in the sense I propose, an underdeveloped system. If we consider that the labour market has also evolved and the "male breadwinner model", in which men had the responsibility of earning a living and women the responsibility of caring for children and the elderly, is in decline in more developed countries, the burden of family care should be systematically reduced as women enter the labour market and emancipate themselves from the gender roles linked to care that society has historically imposed. Care systems will develop as unpaid care work in the family moves mainly into the public and private sectors, from informality to formality.

A brief overview of European care systems: Spain' s case

According to the classification of ideal welfare regimes, there are four types of regimes in Europe1 : the Nordic - the northern European countries and also the Netherlands -, the Anglo-Saxon - the United Kingdom and Ireland -, the continental - Austria, Germany and France - and the Mediterranean - the southern European countries. This classification is indicative, since some of the countries included in these schemes share features with others - such as the Netherlands or Portugal. One country's membership of one regime or another is therefore subject to debate, although a quick summary could be as follows: the Nordic model has a broad public protection system, the Anglo-Saxon one has a more developed private sector, the continental one is situated at a public-private mid-point and the Mediterranean one - also known as the family or family-oriented model - places the family at the centre of care - informal and feminine.

Spain, in southern Europe, is considered to have a Mediterranean care regime. Despite the incorporation of women into the workforce, and the fact that the "male breadwinner" social model is being abandoned, the weight of the family remains considerable due to a series of structural deficiencies. The Dependency Act recognises dependent persons as subjects with full rights, also recognising the burden of care on families, making public what belonged to the private sphere2. However, the financial crisis -which affected women more than men in terms of employment, as in most economic crises-, austerity policies and the reform of the law in 2012 via a Royal Decree have prevented a faster transition towards the formalization of care: the contributions (co-payment) of dependents were regulated and the budget allocation for dependency that the Autonomous Communities received from the State was reduced.

An opportunity: job creation

The scenario of demographic and social change will mean an increase in public spending pressure: more older people will need care and the care that women used to provide on an unpaid basis will not be provided in the same way in the current and future social model. Therefore, one of the opportunities offered by ageing in this respect is job creation. This is indicated by some projections of labour market developments for workers in the care sector: demand will increase in the coming decades. However, the employment created will not provide similar working conditions in all countries, as the quantity and quality of such employment will depend on the policies implemented. A large body of literature - for example, this work - has shown that the care sector in most European countries is characterized by low wages, poor working conditions, little opportunity for job development, high vacancy rates and turnover. Thus, if we aspire to quality care, ensuring adequate conditions for long-term care workers will be crucial. Vocational training of care providers will be essential to meet this aim.

Ageing, care systems, changes and migrant care

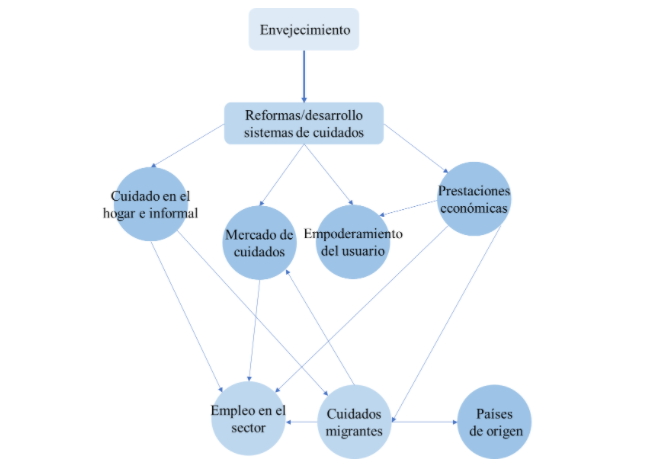

Research -still unpublished- which I co-authored with part of my research group concludes that formal employment will be created in countries where cash benefits for care are conditional on the recruitment of staff. In those countries where such cash benefits are not conditional, a grey care market with a high participation of migrant workers - especially migrant women - will be favoured. It also highlights that the outsourcing of care services has led to a deterioration in working conditions, and that the care market is poorly regulated and clearly differentiated from other existing markets. The links between ageing, care systems and reforms, employment and migration are expressed in the figure below.

Figure. Ageing, care, employment and migration

Ageing has favoured the reform - or development where it did not exist - of care systems and these policies share some characteristics in different countries: the intention to create a care market, to maintain care in the home - formal or informal - and the boom in economic benefits, in order to save other costs and give more freedom to the user, empowering him/her. As I indicated in a previous paragraph, formal employment is created when the use of cash benefits was conditional on the hiring of staff or certain services. However, the problem arises in those countries that have these unconditional cash benefits, with an informal care market: families turn to this unregulated, low-cost and highly flexible market with a large migrant workforce. This produces a crowding out effect or the expulsion of other formal and more costly alternatives. In this case, the overall effect is twofold: it increases the weight of migrant carers, while at the same time increasing the precariousness of work in the sector. Moreover, this effect is currently not only present in countries with the least developed care system - such as the Mediterranean - but, due to cutbacks, it is also emerging in other countries with a tradition of formal care. The situation of migrant women carers is delicate: although they have been able to receive a higher salary than they would in their countries of origin and have helped to contain the pressure of demand for carers, they are exposed to very long working hours, being especially vulnerable to exploitative working conditions, often receiving their salary under the table. Add to this the insecure status linked to immigration and the ability to develop caring relationships with carers can be weakened. And, as Isabel Shutes points out, the exploitation of migrant labour limits the quality of care, as the quality of care is dependent on caring relationships, not exploitation.

On the other hand, as some countries have specialised in exporting migrant labour to specific destinations in order to earn income for the country via remittances, the question arises as to what happens to care in countries of origin. This has been called the global care chain4. While domestic and care sector employment, although precarious, may be created in destination countries, labour market development in source countries is restricted because part of the labour force is working in destination countries.

Concluding

Ageing offers a great opportunity: to create formal employment in the care sector. This could help consolidate the ageing economy, the silver economy, and make it a relevant productive sector in the global economy. To create jobs, if financial benefits are available, they need to be made conditional on the recruitment of formal staff and services to ensure that both the employment status of the employee and the quality of care provided are of good quality. Failure to develop public policies in this direction could encourage the expansion of the informal, grey and informal care economy, potentially affecting states, families, carers, migrants - and their countries - and people in need of care. And if we are to achieve quality care, a developed, fair, equitable and flexible care system, the formalisation of care is important.

1A fifth model can be considered, that of Eastern Europe, with countries such as Hungary, Poland or Bulgaria.

2In Durán, M. Á. (2018). The invisible wealth of care. University of Valencia, p. 105.

3A similar figure has been used in unpublished research.

4En Hochschild, A. (2000). Global Care Chains and Emotional Surplus Value. In W. Hutton & A. Giddens (Eds.), On the edge: living with global capitalism (pp. 130–146). Sage Publishers. http://www.tandfebooks.com/isbn/9781315633794