What are we talking about when we talk about "new longevity"?

Understanding longevity is not an easy task, especially if it is one's own longevity. When we try to talk about it, at the very least, it involves looking at ourselves, in a clear exercise of introspection. We visualise ourselves in a future that is both our own and at the same time uncertain. The new longevity places quantitative and qualitative aspects in a single framework, which means that people have the possibility of living this time with a different intensity, motivations, projects, quality of life and well-being. The new longevity is a unique opportunity that we have as a society; no other generation has had the privilege of imagining ourselves as long-lived as we do today.

Day by day we are witnessing a new phenomenon that not only does not yet reflect an increasingly noticeable reality, but also confronts us with a situation that has not yet managed to permeate society in the new millennium. Especially in societies that are neither European nor North American, where this new culture is slowly, and not without effort, opening up step by step. We are talking about the new longevity.

Towards a new paradigm

Understanding the idea of longevity is not simple, especially if it is one's own longevity. Talking about it implies not only talking about oneself but also about the other, in this case the elderly as "the other(s)". Talking about longevity implies at least looking back at oneself in order to be able, in an exercise of introspection, to visualise ourselves in a future that is both our own and at the same time uncertain. And what's more, it is a stage that society is only now preparing to discover with a certain amount of embarrassment. It is only a matter of observing how the media and how we people talk about the passing of time, about growing old. It tends to be externalised, it is placed in the other. It is left out. A subtle and sometimes not so subtle way of outsourcing an unresolved issue. The natural is denaturalised. Old age, the passage of time as such, is not sexy. The old is him or her, it is not me. Old age lacks its own moment in our consciousness as there are other moments or stages in the life course. We all know or have heard of the needs and rights of children, of how complex and problematic adolescence often is, or of the mid-life crisis. Childhood, adolescence and even widowhood are recognised as natural stages of life. However, the new longevity is not only due to this redefinition but also to its incorporation into our lives.

In its second meaning, the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy states that a paradigm is a theory or set of theories whose central nucleus is accepted without question and which provides the basis and model for solving problems and advancing knowledge. It is a concept that refers to those relevant aspects of a situation that can be taken as an example. They are often used to explain processes and help to establish what is "normal or legitimate" as knowledge and intervention, as long as they are consistent with the current paradigm.

Looking back in history, the 19th century was the century of the Industrial Revolution, a time when the prevailing paradigm was based on the power of physical capital. In that century, social changes were of a magnitude previously unthinkable. The economic, social and technological transformation that had begun in the second half of the 18th century in Britain continued for decades to spread to Europe and North America, concluding between 1820 and 1840. Then came the 20th century, the century of education and the advantage of having been able to access it as a way of creating human capital. This made a difference and stratified much of society. It was also the time of the first demonstrations for children's rights. In 1870 the United Kingdom made primary education compulsory for children, and in 1852 Massachusetts was the first American state to make this right compulsory. This was a reaction to the consequences of the Industrial Revolution on child labour and the need to regulate it. Later, in 1924, Save the Children founder and social activist Eglantyne Jebb drafted in Geneva the first Declaration for their rights, which led to the 1959 Declaration for the Rights of Children within the framework of the United Nations. As can be seen, social constructions lead to real changes, changes which, on the other hand, take a long time because they require a consensus. Therefore, the new longevity must be thought of as a new paradigm that goes beyond health and well-being. It is a 360-degree vision. It places those of us who are over 50 in a role of strong protagonism from the social, consumption, production of services, governance, but where health, wellbeing and quality of life also become determining factors. The age of 50+ is often presented to people as a hinge moment, loaded with symbolism that represents the arrival of half a century of life. A figure, if you like, round and thought-provoking. The age of 50 often confronts us with who we are, who we think we are and who society - often - imposes on us that we should be. At 50 we are no longer young, but neither are we old people in the classic way. We have already lived, we have already travelled a long way, there are losses, but also many gains in the form of family and children, professional recognition, economic fulfilment and many others of a personal nature that are difficult to measure. The list could go on, but what should be clear is that in the new longevity, in principle, people in their 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s and beyond are included; in fact, the new longevity should begin to be a subject of teaching and learning in primary schools, not only because intergenerationality will be the resource for building the new society, but also because it is a subject that affects us all as a community.

The hard data shows that the 50+ sector of the population controls about 75% of the US household economy, with 10,000 people turning 65, a phenomenon that will occur until 2030, or that since the Juncker Commission in the European Union published the first report on the Silver Economy it is difficult to comprehend the paradigm shift we are witnessing.

The new longevity is a unique opportunity we have in this 21st century. No previous generation in human evolution has had the privilege of being able to imagine themselves as long-lived as they are today. The disadvantage, however, is that virtually all of our society is still managed, structured and thought through the frameworks of the last century. Principles and ways of thinking from more than a century ago, such as the idea of a rigid life course, the obligatory retirement from work and others as diverse as sexuality, or grandparenthood as the only family role, even if it is not to our liking.

The data "age" as an indicator that anchors us in categories of a rigid social scheme is beginning to be revised by the new cohorts of older people and the new longevity. Years ago, the American psychologist Bernice Neugarten raised the difficulty of labelling or standardising ages when more and more men and women decide to fall in love and marry, and why not also to divorce, beyond the age of 70. Did you know that these days in Central Europe the age of marriage for women is around 32 and 35 for men? Or that the birth of the first child in this region of the world is around 30 years of age? The phenomenon of women and men leaving and returning to the labour market, starting second and even third careers2 is becoming more and more common. This is why it is very difficult to establish precise limits. Talking about longevity is not new. In the Roman Senate, most of its members were older, double the life expectancy of the time. When Don Quixote decided to set off across the fields of Castile-La Mancha, he did so at the age of 50! And its author Miguel de Cervantes wrote it at the age of 56. Two long-lived people for the time, author and character.

The word longevity refers to the length of life, something which, as we all know, has been increasing significantly throughout the world over the last hundred years. But the social construction that we have classically experienced about older people and their narrative places them in a situation where old age is seen as just a miserable version of middle age. A narrative that is based on the passive role of the elderly and the recipient of assistance, and that today is reduced to the last years of people's lives (although not in all cases). In the words of Simone de Beauvoir: "But if old age, as a biological destiny, is a transhistorical reality, it is no less true that this destiny is lived in a variable way according to the social context". Therein lies our challenge and the object of this book: learning to live the second half of our lives. A process of constructing one's own longevity and, by extension, a change in the social narrative.

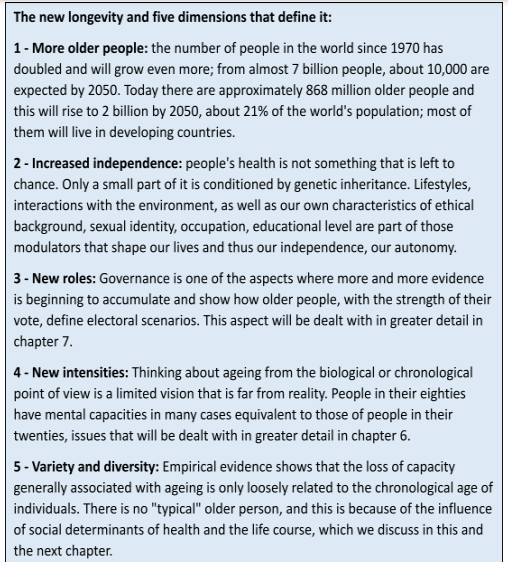

The new longevity frames and integrates the quantitative aspect with the qualitative aspect that makes it possible for people to live this time with a different intensity, motivations, projects, quality of life and well-being. We can identify several dimensions that define it3.

Table 1.

I am one of those who do not like definitions because to define is to limit and often to label in order to segregate; even more so in the case of older people where today there is no single definition, neither functional nor administrative, agreed on what it is to be older or who is older. The study Predictors of attitudes to age across Europe4 showed that within Europe the onset of old age as perceived by people varies from 59 in the UK, 63 in France or 68 in Greece. There are also differences according to people's age, where for example in Spain5 , for those aged between 20 - 29 years old one is an older person at 66, for someone aged between 50 and 59 years old one is older at 68 and for those aged 80 years and over one reaches the age of 70. On the other hand, experience shows that three very different people are those in their 60's than someone who has just crossed their 70's and someone over 80's. Let's put it this way, they are three different subspecies in the same ecosystem, not counting the "youngest" 50+.

Growing old can and must be learned. The passage of time, longevity, has always been a personal and individual experience, but for the first time in history it is beginning to be a collective experience, a social phenomenon; therefore it is at the same time curiosity, learning and construction. It is up to us and our decisions how we will face this stage of the life course. Being old is a possibility that will present itself to most of us on average, being old and seeking to be happy is something that depends on each one of us and is a subjective decision that each one of us will determine at some point in our lives. The magnitude of the undertaking is far from easy. That is why this book was written with the purpose of seeking a personal and collective change in the way we think and live the second half of life. From the consideration imposed on us by the relevance of the social determinants of health, the life course, the different levels of molecular complexity such as the section concerning telomeres, or the aspects linked to physical activity and lifestyles, two interventions that have shown their effect on longevity. So you will not find miracle cures or fountains of youth, but resources, ideas and evidence that can help make life ahead healthier and more fulfilling.

To say that the future has arrived requires, at the very least, a deeper look beyond the quantitative aspect and allows us to shed light on the meaning of this global phenomenon. In an environment with certain good living conditions, it is estimated that three out of four people in their 60s will reach their 80s; two out of three will reach their 85s and one out of two will reach their 90s. Today a person turning 50 has a 50% chance of reaching the age of 956. New stages bring with them profound social and institutional changes; changes that our societies and governments are often slow to recognise and assimilate. Indeed, our institutions still operate on models that are still too rigid, many of them over a hundred years old, outdated for 21st century ways of life.

The change is not only quantitative, but also qualitative. New roles define this new longevity and help to understand the extent of its influence. This is seen in older people who vote, consume, produce and provide service. We saw this in the so-called Brexit in the United Kingdom7 and in the last election in the United States8 where they made themselves felt, and strongly so, as their votes decisively conditioned the outcome of these elections.

Today, older people are a more educated generation and this allows them to inform themselves, to learn, to change their lifestyle and, above all, to challenge the established canons. Retirement or retirement is no longer a rigid and imposed stage of supposed "recreation", but a stage of "re-creation", in which intangible values gain strength as never before. More and more people are retiring or retiring from what they do NOT like to start new challenges.

Today's older generations are the first who are living longer than they thought they would, than the generations that preceded them most likely did. Therefore, they are a generation that did not know how to or could not plan for this new stage. The next generations will do so. We will try to do so already knowing and seeing what this new longevity means. This is undoubtedly a great advantage, but it may or may not be good news.

Our existence and life experience are shaped by our own unique life course determined by the conditions that surround us from birth in our home and community9 . Conditions that accompany us in our growth and development, with their opportunities or disadvantages, make each older person unique. The variety of "adulthoods" and "old age" is a feature and identity of this new stage of life. A new life and a new longevity are part of our destiny.

In conclusion

It is becoming more and more common to see people in their 60s deciding to start new university degrees or to finish those that are still pending. If it is as they say, that more than half of the jobs of the future have not yet been invented, should I be prepared to adapt when - after my formal retirement - I want to remain in the labour market? How will I modify the house where we live with my family in the future? Should a move be planned at some point? When is or will be that moment?

The new longevity is a root change we are living through and will become more and more significant as we 50+ look to and model ourselves on today's elders and decide what we want for ourselves. Unlike them, in our case, we can plan, build and even implement other ways of life. What about personal bonds? We have lived and developed our family lives with fewer children than previous generations or with children who are already moving in an increasingly interconnected and borderless world. We will also have to ask whether love with the same person can last so long.

The new longevity requires perspective, understanding its opportunities and challenges. New issues are already on the social and personal agenda and we have a hard task ahead of us to find solutions. We need to raise in many countries where it is not yet discussed, issues such as a dignified end of life and the training of human resources, the recognition of caregivers and their training, the need for flexible retirement schemes, as well as social protection in those countries where it does not exist, opportunities to promote intergenerationality, to stop talking about happiness as an aspirational utopia in order to seek well-being and to understand that health is a capital that is cultivated from the first years of formal schooling.

The new longevity will be the space where most of us will probably live, and like any new paradigm, it requires a perspective that allows us to understand that living longer is not only more opportunities for each of us and for society, but also a reason for human celebration. Welcome!

1. Neugarten, Berenice, . Los significados de la edad, Editorial Barcelona 1999.

2. Scott AJ. The longevity society. Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2021 Dec;2(12):820-e827.

3. Bernardini D., La segunda mitad, los 50+, vivir la nueva longevidad. (2019) Ed. Aguilar, Argentina.

4. Abrams D., Vauclair CM., Swift H., Predictors of attitudes to age across Europe, University of Kent, Reino Unido (2011).

5. Abellán García A., Esparza Catalán C., (2009). “Percepción de los españoles sobre distintos aspectos relacionados con los mayores y el envejecimiento. Datos de mayo de 2009”. Madrid, Portal Mayores, Informes Portal Mayores, nº 91.

6. The economics of longevity. Special report, The Economist, Julio 8, 2017.

7.How Britain Voted. Over-65s were more than twice as likely as under-25s to have voted to leave the European Union. Junio 27, 2016

8. How groups voted 2016. Roper Center for Public Opinion Research. Cornell University.

9. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives - Ben-Shlomo Y., Kuh D. International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol 31(2)1 285–293, 2002.

Pregunta

Respuestas de los expertos

Respuestas de los usuarios

Nowadays it is not easy to live a long life. While it is true that medicine has helped us to have a better quality of life and thus to be more independent and active, it is also true that family life has undergone major changes and not exactly for the good of the long-lived family member.

Society as a whole lives outwardly, work takes up many hours of young people's time, sports and activities with friends of their own age take up a lot of their time, and just as young children do not have the company and support of their parents, so long-lived parents have lost the company of the family environment that is so necessary.

Man is a social being but the family is his first and last society, then there is the outside world and its benefits. Sometimes, when the long-lived relative loses abilities (and realises it) he can no longer play sports or go for a walk alone, he can no longer sew, knit or do heavy work around the house... longevity weighs heavily. I take refuge in reading, a bit of TV and when I see my grandchildren my heart bursts with happiness. ....