National Transfer Accounts in Spain 1900-1970 - Part II

The developed countries are immersed in a strong process of demographic transition, which has led them to be characterized by the presence of high birth rates and mortality to a new situation marked by the low number of births (very often below the rate of population replacement) along with significant increases in life expectancy. Spain is precisely one of the countries in which this demographic change is being most marked, since its life expectancy is among the highest in the world, while its fertility rate is among the lowest.

The aim of this project is to carry out a historical analysis of how demographic evolution has interacted with economic development in Spain. Traditionally, the analysis of economic evolution has been carried out separately from demographic evolution. However, in the last decades new works have been interested in the relationship between economy and demography, not only in what refers to past evolution, but above all, for the future. The objective is to understand the interaction between the two types of variables, and to draw lessons that will allow us to face with guarantees the strong ageing process in which today's society is immersed.

The interest of this project is, particularly, the analysis of the evolution of the so-called welfare state in Spain from its first manifestations at the beginning of the 20th century to its consolidation with democracy. The aim is to analyse how different social policies have evolved since their inception, how they have interacted with the role of families in social organisation and intergenerational transfers, and what the effects have been on economic and social development.

Methodology: National Transfer Accounts (NTA) and their adaptation for historical estimates.

The life cycle of people implies that only during certain ages are they able to generate the resources necessary to meet their consumption needs throughout their lives. During childhood and retirement, people need some form of financial support, either from the family or the state, to meet their needs. In the case of older people, there is a theoretical possibility of also resorting to intertemporal income reallocations (savings while working to evict in old age). Currently, family transfers are the main source of resources for children, while public transfers (pensions, health) are the main source of resources for the elderly. However, this has not always been the case. The welfare state as a source of transfers for the elderly has developed and consolidated throughout the twentieth century, largely replacing family transfers.

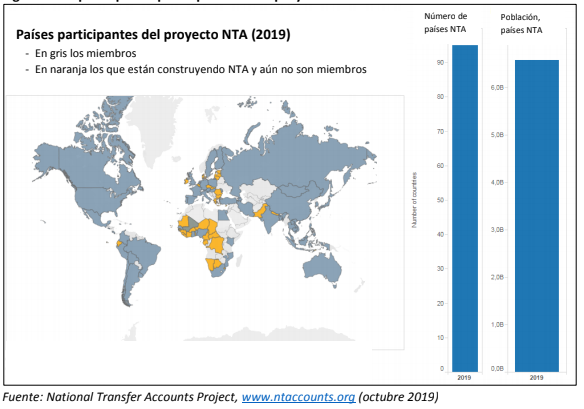

Until recently, very little data was available to accurately analyse intergenerational transfers. However, since the early 2000s a new methodology has been developed that allows for the estimation of all resource flows between individuals of different ages living together at a given point in time. These are the so-called National Transfer Accounts (NTAs), an international project led by the American Universities of Berkeley and Hawaii in which more than sixty countries from all over the world are currently participating, including Spain (see Figure 1). The methodology for estimating NTAs has been approved and published in a manual by the United Nations (Population Division).

Figure 1. Map of countries participating in the NTA project in 2019

ATNs consist of estimating, for each moment of time and for a given economy (for the moment the analysis is carried out only by countries), all the resource flows that take place between the different age groups of the generations that live together. The ATNs do not only provide profiles of consumption and labour income, but also of all the variables into which these can be broken down, as well as of the different mechanisms for financing the consumption needs of the different ages. Thus, profiles are constructed by age of private transfers (both family and intra-family), and public transfers (all taxes, social contributions and all public expenditure). All profiles are obtained per capita and, subsequently, at an aggregate level (multiplying each profile by the population in each age group). The aggregates must match those provided by each country's National Accounts, so that the ATNs are consistent with the National Accounts.

The estimation of ATNs implies a heavy workload due to the need to use large micro databases, from which per capita profiles are obtained. These databases must be complemented, in some cases, with other administrative data sources and, subsequently, all age profiles obtained must be adjusted to the National Accounts aggregates to ensure consistency between the resulting magnitudes in both methodologies.

The estimation of ATNs requires microdata of income and consumption that allow their imputation by age. For Spain, income microdata must be extracted from the Living Conditions Survey (EU-SILC), while those corresponding to consumption come from the Household Budget Survey (HBS). However, these surveys are not available when making historical estimates. The first Household Budget Survey in Spain was carried out by the INE in 1958. However, given that its objective was to study the consumption patterns of the average Spanish household, it excluded certain types of households such as those with high incomes or with unemployed heads of household. In 1964, the INE carried out a second Household Budget Survey, this time with no restrictions on the population surveyed and with much more detailed information on both income and family expenses. The detail of the information was again improved in the Survey carried out for 1973-74. Unfortunately, none of these three EPFs contains the information necessary to directly apply the NTA methodology. For 1958 and 1964, microdata are not available, while for 1973-74, microdata are only presented at the household level, without giving details about the composition and characteristics of its members, so it is not possible to impute the information by individuals and ages.

Thus, the application of the NTA methodology is only properly applicable to Spain from 1980 onwards. The situation is quite similar in the rest of the countries. However, having NTA in a sufficiently long period of time would be of great interest to understand processes such as the demographic transition or the development of welfare states and their impacts on societies. In most countries, the construction of welfare states began in the interwar period. In Spain, despite doing so later, it also began well before 1980: in that year, public social spending represented 19.2% of GDP, whereas in 1960 it was barely 4.4% (Espuelas, 2013).

Thus, despite not having the microdata needed to construct ATNs before 1980, the aim of this project is their indirect estimation through the use of different alternative data sources, such as population censuses, public accounts and other statistical publications. Although the quality of these data decreases with time, we consider that there are adequate data for estimation at least during the second half of the twentieth century, and with some reservations for the first half. By way of illustration, here are some very preliminary results obtained from some components of the ATNs in 1960, compared with those obtained in subproject 2.

For the estimation of the 1960 income and consumption profiles, the series of GDP and private consumption in Spain estimated by Prados de la Escosura (2017) for the period 1850-2015 have been used. According to this source, the Spanish GDP in 1960 amounted to 3,818 million euros, while private consumption (of households and other non-profit institutions) represented 2,759 million euros. On the other hand, labour income data come from Prados de la Escosura and Rosés (2009), which estimate that in 1960 it represented 70% of GDP, which is equivalent to some 2,673 million euros. In order to distribute these figures aggregated by age, information from different data sources has been used. In the case of labour income, the age structure of the working-age population from population censuses has been used, as well as different hypotheses on the relationship between wages and age, based on data for later dates.

For private consumption, the standard NTA procedure has been followed for the application of an equivalence scale. Subsequently, different categories of public consumption by age have also been distributed. Thus, the age distribution of public education consumption has been based on public expenditure data by educational level collected by the Institute of Fiscal Studies (1976). Regarding health, the aggregated data for 1960 have been taken from Espuelas (2013) and have been distributed taking into account the relative size of the different institutions specialised in health care, with data from the Statistical Yearbooks.

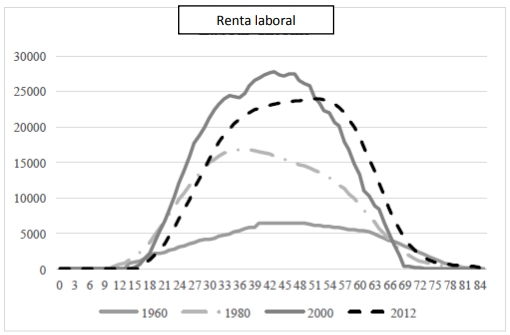

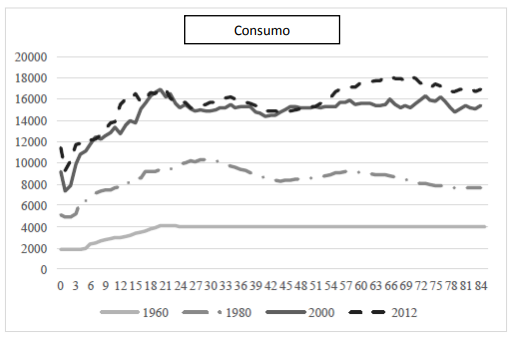

The final results have been expressed in 2012 euros to compare them directly with the NTA available for subsequent years, obtained in subproject 2 of the coordinated project. Figure 1 shows the main NTA, labour income and consumption profiles. As can be seen, the series for 1960 correspond to a much poorer economy (GDP per capita in 1960 represented only 36% of that corresponding to 1980). As a consequence, the period of labour activity was much longer: from the age of 12 onwards, positive figures can be seen for labour income, which does not disappear until the age of 75. On the other hand, although the shape of the profile by age shows the typical form of U-invested, it is much less appreciable than in subsequent periods, with much lower income differences between those obtained at younger and older ages and those of the central period of life.

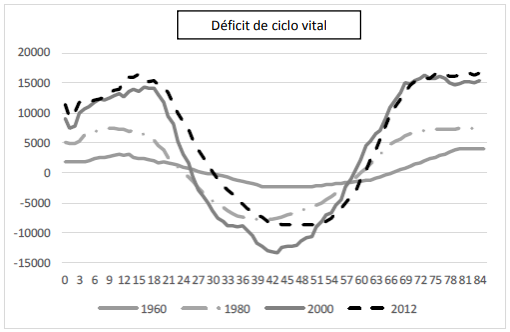

As a result, the life cycle deficit profile (LCD) is also quite different from subsequent periods. First, life cycle surplus occurs over a much longer period (it extends to 66 years). On the other hand, the level of the LCD, both when positive (childhood and old age) and negative (central ages) is considerably lower.

Profile of labour income and consumption per capita in Spain (1960, 1980, 2000, 2012) (euros 2012).

Figure 3. Life cycle deficit (LCD) per capita by age in Spain: 1960, 1980, 2000, 2012

Next objectives

During this first period, this subproject has been developed in close coordination with subproject 2. This last part of the most recent data allows the full development of the NTA methodology and goes back in the past by reproducing the estimates as far as possible. Subproject 1, on the other hand, develops in the opposite direction, searching for the oldest historical sources available by applying historical research techniques that make it possible to identify the impact of National Accounts by age.

The next objectives are:

- To refine the preliminary estimates made for 1960 and extend the estimate to other years, to the extent permitted by identified historical sources. - Detailed analysis of the results in conjunction with sub-projects 2-4.

Most relevant bibliographical references

Abio, G., C. Patxot, E. Rentería and G. Souto (2015). “Taking care of our elderly and our children. Towards a balanced welfare state”, in M. Gas-Aixendri and R.Cavalloti, Family and Sustainable Development, Thomson Reuters, pp. 57-71.

Albertini, M. (2016). Ageing and Family Solidarity in Europe: Patterns and Driving Factors of Intergenerational Support. Policy Research Working Paper 7678, Poverty and Equity Global Practice Group., World Bank Group.

Bloom, D.E. and J.G. Williamson (1998). “Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia”, The World Bank Economic Review, 12(3), 340-375.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2002a). Why we need a new Welfare State. Oxford University Press.

Espuelas, S. (2013). La evolución del gasto social público en España, 1850-2005. Madrid, Banco de España, Estudios de Historia Económica N.o 63.

Instituto de Estudios Fiscales (1976). Datos básicos para la historia financiera de España, 1850- 1975. Madrid, IEF.

Mason, A. and R. Lee (2011). “Population aging and the generational economy: Key findings”, in A. Mason (Eds), Population Aging and the Generational Economy. A Global Perspective, Edward Elgar.

Lee, R. and A. Mason (2011). Population Aging and the Generational Economy. A Global Perspective, Edward Elgar.

OECD (2014). Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-en.

Patxot, C., E. Rentería, M. Sánchez-Romero and G. Souto (2011). “How intergenerational transfers finance the lifecycle deficit in Spain”, in R. Lee and A. Mason, Population Aging and the Generational Economy. A Global Perspective, Edward Elgar, p.241-255.

Patxot, C., E. Rentería, M. Sánchez-Romero and G. Souto (2012). “Measuring the balance of government intervention on forward and backward family transfers using NTA estimates: the modified Lee arrows”, International Tax and Public Finance, 19, p. 442-461.

Patxot, C., E. Rentería and G. Souto (2015). “Can we keep the pre-crisis living standards? An analysis based on NTA profiles in Spain”, Journal of Economics of Ageing, 5, pp. 54-62.

Prados de la Escosura, L. (2017). Spanish Economic Growth, 1850-2015. London, Palgrave MacMillan.

Prados de la Escosura, L. y J.R. Rosés (2009). “The Sources of Long-Run Growth in Spain, 1850– 2000”. Journal of Economic History, 69 (4), pp. 1063-1091.

Rentería, E., G. Souto, I. Mejía-Guevara and C. Patxot (2016). “The effects of education on the demographic dividend”, Population and Development Review, 42 (4), p. 651-671.

Sánchez-Romero, M., G. Abio, C. Patxot, G. Souto (2018). “Contribution of Demography to Economic Growth”, SERIEs Journal 9, pp. 29-64.

UN (2013). National Transfer Accounts Manual. Measuring and Analysing the Generational Economy. Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, New York.