For centuries, humanity measured its progress by counting years.

Each decade that extended life expectancy was celebrated as a conquest.

But today, in a society that has already gained time, a more decisive question emerges: how much of that time is truly lived with health, autonomy, and well‑being?

The project “Healthy Life Expectancy in Spain”, promoted by CENIE and developed by the Center for Demographic Studies (CED), answers that question with scientific rigor and unprecedented ambition.

Led by Iñaki Permanyer, ICREA researcher, and with the participation of Aïda Solé‑Auró, Elisenda Rentería, Jordi Gumà, Jeroen Spijker, Sergi Trias, Pilar Zueras, and Albert Esteve, the study has placed Spain at the forefront of analysis on how longevity translates — or not — into real well‑being.

A New Map to Understand Health

The project was born with a dual purpose: to measure and to understand.

To measure, because traditional indicators — life expectancy or mortality rates — are no longer enough to describe the complex life trajectories of an aging population.

To understand, because behind the data are lives: generations, genders, and territories that experience longevity in very different ways.

The CED team is, for the first time in Spain, combining national health surveys, mortality records, and anonymized clinical databases of more than 1.5 million people in Catalonia, thanks to the PADRIS program.

This integration of data — unprecedented in scale, precision, and scope — allows researchers to observe not only when we die, but also when and how disease begins, how long it lasts, and how it varies by sex, education, or social condition.

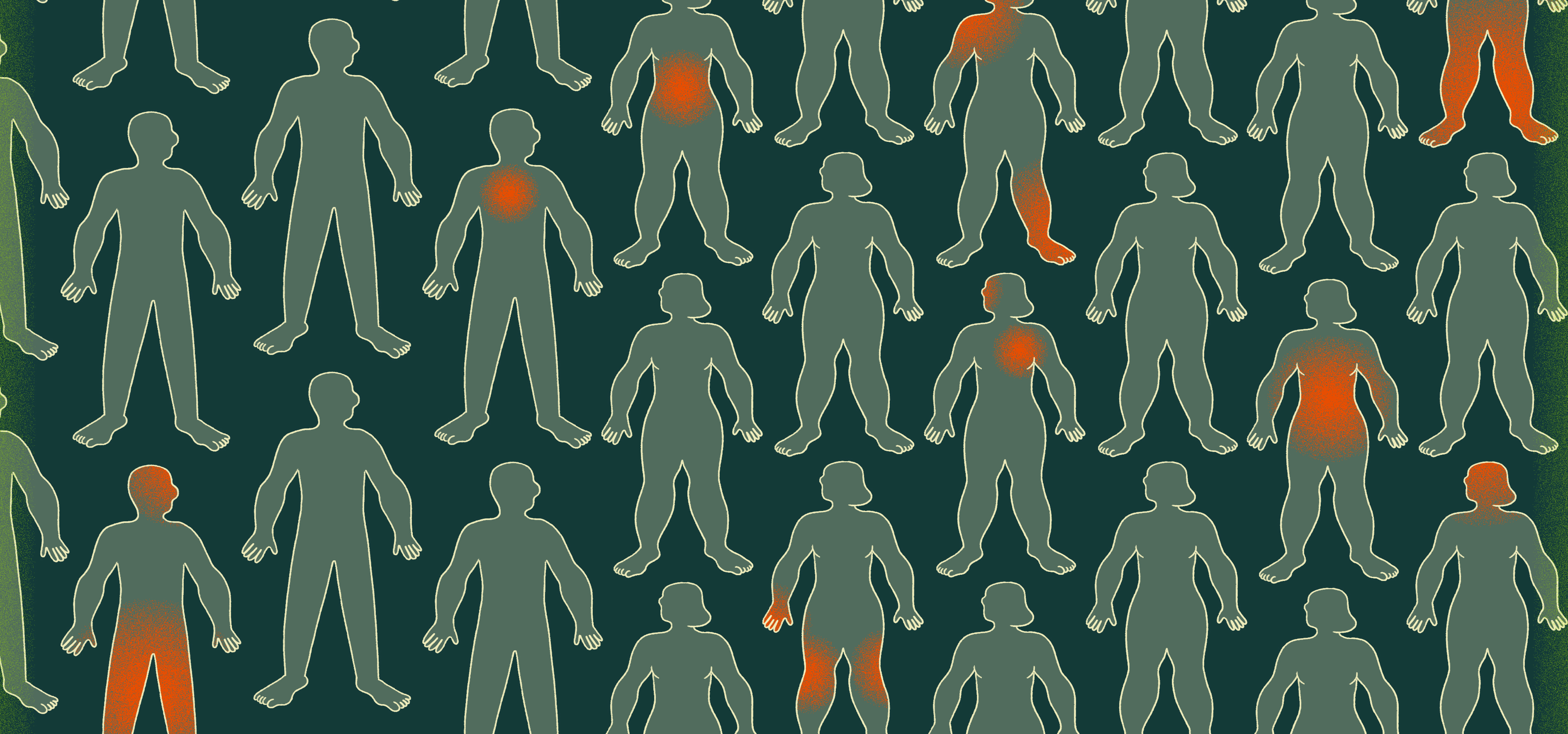

The study analyzes four key dimensions:

- Territorial evolution, to draw a map of regional health inequalities.

- Gender differences, to understand why women live longer but also spend more time with illness.

- The socioeconomic gradient, showing how education and income determine the years lived in good health.

- Medical causes, to identify the diseases that most widen the gap between longevity and health.

The Female Paradox: Living Longer, But Not Always Better

Among the revealing findings is the contribution of Aïda Solé‑Auró, who explores the relationship between gender, education, and health.

Spain, one of the countries with the highest life expectancy in the world, shows a paradox: women live longer but accumulate more years with chronic pain, limitations, or cognitive decline.

Her analysis demonstrates that education acts as a silent vaccine.

A 45‑year‑old woman with basic schooling may live up to eight more years in poor health compared to another with a university education.

For men, the difference also exists but is almost halved.

Being a woman with low educational attainment represents a double disadvantage: greater risk of illness and less autonomy in old age.

As younger, better‑educated generations age, the gender gap could narrow, but Solé‑Auró warns that progress is not automatic.

Investing in education remains one of the most effective yet least recognized public health policies.

“Thinking about health,” she affirms, “is not just about strengthening hospitals: it is about ensuring equitable education from childhood.”

Generational Drift: A Silent Warning

Meanwhile, Iñaki Permanyer has documented a troubling phenomenon: “generational drift in health.”

From analyzing health and mortality records in Catalonia between 2010 and 2021, his team found that younger generations show higher levels of multimorbidity — suffering several chronic diseases simultaneously — than earlier cohorts at the same age.

Among women born in the 1990s, for example, the prevalence of multimorbidity at age 25 is 50% higher than in those born a decade earlier.

This could mean that, for the first time, the children and grandchildren of those who conquered longevity may age in worse health than their parents.

The cause, according to Permanyer, is multifaceted: social inequality, rising mental disorders, obesity, sedentary lifestyles, and increasingly early diagnostic detection.

The finding is not meant to alarm but to anticipate.

The challenge — says the researcher — is to transform knowledge into prevention: designing evidence‑based policies, promoting healthy habits from youth, and strengthening epidemiological surveillance before inequalities become entrenched.

From Measurement to Action

The Healthy Life Expectancy in Spain project does not aim merely to describe reality but to transform it.

Its indicators will guide more precise policies, design regional interventions, and define preventive strategies that integrate social and health dimensions.

Its value lies not only in science but in the structural vision it proposes: understanding health as a common good, longevity as a collective responsibility, and prevention as a national policy.

In CENIE’s vision, this research is more than a study: it is a knowledge base for the future OLAS Observatory, which will unite clinical, social, and territorial data to anticipate risks of frailty and design community‑based and personalized programs.

The project thus consolidates CENIE’s role as a space where science, politics, and culture meet to rethink what it means to live longer.

The Legacy of a New Paradigm

The great value of this work is that it translates a human intuition into numbers: living longer only makes sense if we live better.

And to achieve this, we must understand the inequalities that still persist among territories, generations, and genders.

With the collaboration of the CED, Spain positions itself at the forefront of a global movement seeking to redefine health not as the absence of disease but as the capacity to live fully.

This is, without doubt, one of CENIE’s major scientific and social milestones of the year: a project that not only measures well‑being but helps imagine how to build it.