Loneliness in old age: an inseparable relationship?

In Spain, according to the Continuous Household Survey (INE), 2,037,700 persons over 65 years of age live alone. This figure, together with certain beliefs, makes old age and loneliness automatically related. There are also 2,694,800 people under 65 living alone, although this figure tends to receive less attention. Does this mean that there are no problems of loneliness among the general population?

This is certainly not true. Loneliness is hard at any age and has been shown to be associated with a number of health problems. For example, some research has linked social isolation and loneliness to increased risks of physical and mental problems. In the same way that stress affects us in a very negative way, our body, our defences, also react to unwanted loneliness. Among the physical problems, suffering from high blood pressure, different heart diseases, obesity, weakening of the immune system. Other problems would be increased anxiety, depression or cognitive decline. Without a doubt we are social beings and we need company (even though we have that valid saying that it is better to be alone than in bad company).

However, we need to distinguish between being alone, voluntarily or involuntarily, and feeling alone, which is different. But also between accusing loneliness in a negative way (suffering it) or enjoying it, even needing it sometimes. There is also the possibility of enjoying some aspects of loneliness and rejecting or suffering others.

The point is that some research on old age automatically focuses on the issue of loneliness, as if old age and loneliness were indissoluble issues. In the press, when people talk about older people, they mostly refer to issues of loneliness. We see this recently, when it is assumed that single-person households in old age are invariably dominated by loneliness. Let us go into this a little more deeply.

It is true that, if we go to the RAE, the first meaning for solitude is the voluntary or involuntary lack of companionship. But it is the third meaning that derives in the conversion of solitude to the sorrow and melancholy felt by the absence, death or loss of someone or something. Even different theories about old age (fortunately replaced by more novel theories) focused on this idea of the disconnection between old age and society, as a natural result of the desire of both parties.

I am not saying at all that loneliness is not a problem at any age. In particular, feeling lonely is terrible. But I refuse to assume that the fact that older people live alone is tantamount to loneliness. Why? Because it would mean denying them a voice in society. It would mean denying that an older person who lives alone can receive visits (beyond families) and make them, that they have friends, that they talk to their neighbours, that they participate in social activities, that they go to the cinema or to demonstrations. And I don't think that's true or that that description defines Spanish old age. One thing that does worry me is that loneliness is imposed, because older people cannot participate in society because their housing prevents them from doing so, for example.

Although the Elderly People's Living Conditions Survey (IMSERSO) dealt with this issue directly, I decided to look at some indirect indicators provided by the 2017 National Health Survey (Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare and INE), which I found very interesting. The ENSE collects health information on the entire population regarding the state of health, the personal, social and environmental determinants of health and the use of and access to health services. It also includes a series of questions on emotional and personal support in daily life, which are the ones we are going to analyse. Each one of the questions refers to a scale of the level of desire. This is exactly what I am referring to. We can feel lonely, let us imagine, but it is not the same to feel lonely sometimes, to feel a little lonely or to feel very lonely. Let us say that we operationalize this complex variable in questions that refer to what makes people feel lonely. I would say, and I know this is subjective, that feeling lonely is not having anyone to talk to when I need to, for example. Or not having a visitor when I want one. Even if these are just examples, the question of needing and wanting (or not) is for me what would define loneliness as something negative, neutral, or positive.

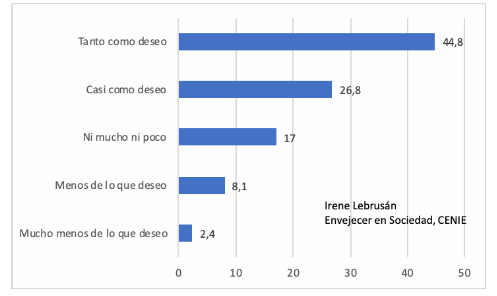

In order to approach our question, I have decided to analyse the situation of people over 65 years of age with regard to the different variables included in the ENSE. The different questions on social support deal with issues related to loneliness on a scale ranging from "much less than I wish" to "as much as I wish". The first question to be analysed is to have visits from friends and family. It is true that 2.4% of older people consider that they have "far less than they wish" or "less than they want" (699,188 people, 8.1%). In contrast, 44.8% of older people receive as many visits as they wish and 26.8% almost as much as they want.

Graph 1: People 65+(%) who receive visits from friends and relatives according to degree of desire. Spain, 2017.

Source: Own elaboration based on ENS 2017

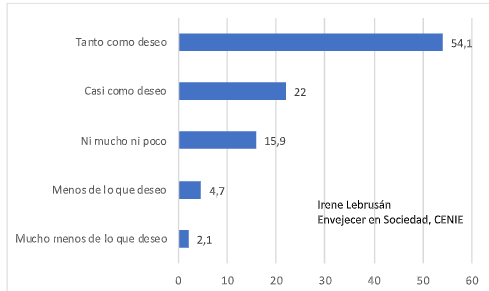

But the second question is even more interesting to me because it involves going out of the house. Do older people receive invitations to go out and be distracted? Well, according to the ENSE, over half of the 65+ receive as many invitations as they want. 22.0% almost as much as they want, 15.9% not much and 10.5% less than they want (2.1% much less than they want).

Graph 2: People 65+(%) who receive invitations to distract themselves and go out with other people by degree. Spain, 2017.

Source: Own elaboration based on ENS 2017

These are just some of the very limited issues to bring us closer to a reality as complex as the question of loneliness. And no, at no time do I claim that (unwanted) solitude is not important. Moreover, I believe that it is a growing social problem, and that it is also related to other problems of social disconnection. We are far from having such a serious problem as in other societies (in the United States it seems to me to be a problem of prime importance), but I do think that we are feeling more and more alone, with all the negative that this entails. The problem of loneliness is serious, with effects on health, but especially on psychological health. Each and every one of us could collaborate to diminish the feeling of loneliness of others. Sometimes it is enough to be friendly, to say hello, to engage in casual conversation on the bus or while waiting at the doctor's office. Because, in addition, the great thing about working in the loneliness of others is that, when we do so, we also work on our own.