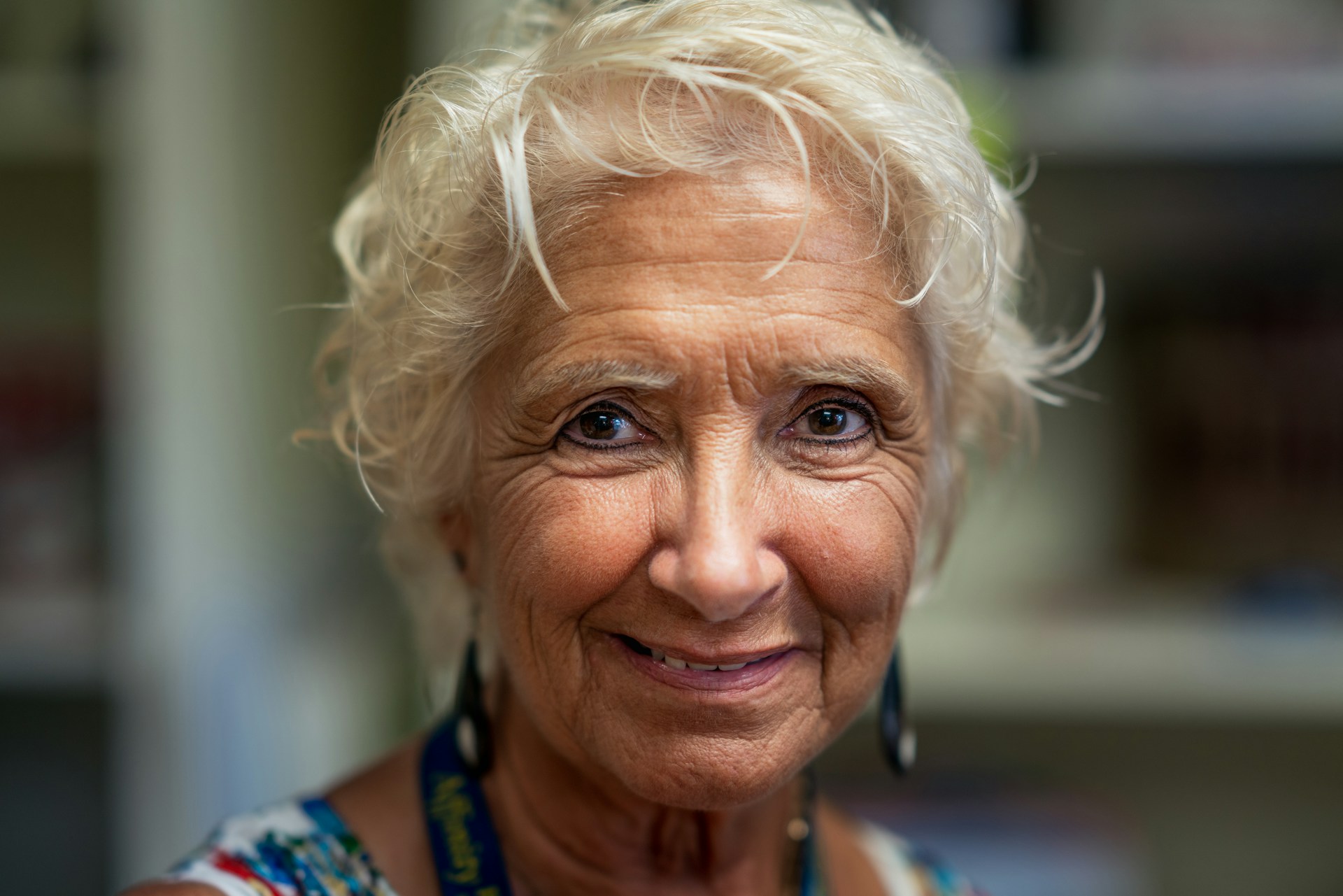

“I miss my husband… As for the rest… no, I don’t miss the rest, because I live, well, what can I say, [I live] like a queen.” The sentence is from Isabel, 89 years old, who, after becoming a widow, moved to what we call a “rotating home,” meaning living under the care and organization of her children and, in practice, spending one month (or another set period) in each of their homes. Her words, with a certain echo of resignation, contain a paradox shared by many older women: widowhood can be both an experience of loss and a renewed form of guardianship. Not always unpleasant, or at least full of love and good intentions, but still a kind of regression to a minor’s condition.

For decades, the story of many women was tied to a marital model in which the husband occupied the role of provider, decision-maker, and authority figure. In an interview with Cristina Almeida, she recalled how there was a time when “a woman, even if she were a lawyer, needed her husband’s authorization to represent someone in court.” This legal and symbolic subordination left lasting marks on the life paths of entire generations (generations that are now, by the way, unjustly treated, in my opinion, by certain ideological sectors). That is why, when widowhood arrives, it is not always experienced only as mourning —as the loss of whoever may or may not have been the love of one’s life. For some, perhaps for many, it is also the moment when a long-standing relationship of dependency is broken.

It also means facing the “outside world” for the first time. Women were socialized to handle domestic matters —meals, shopping— but much less so financial or administrative ones. This means that some women face, for the first time in old age, matters of great importance, such as managing their own assets or a rental contract. A woman, 75 years old at the time, told me how, after being widowed, she was forced to make important decisions on her own for the first time, especially when her landlord decided to sell the apartment she lived in. “If I didn’t buy the house, I had to leave. I was already a widow. He forced me to buy the house.” It was a tough experience, but also a demonstration of capability and autonomy that perhaps she had never been allowed before. Her case was especially difficult because, after the death of her husband and her sister, she was left alone, without the support she had always had. In other cases, however, the husband’s guardianship is simply replaced by that of the children, with speeches as well-intentioned as they are limiting.

Another woman, only 65 years old (the beginning of old age), told me how her children were trying to decide for her after her early widowhood. Without even asking her, they were planning an unwanted move: “Mom, this house is too big for you (…) I already talked to (…) so you can put the furniture…” (…) “No, no, I’m not putting my furniture anywhere!” The —necessary— resistance to being treated as a child appears again and again in the accounts of widowed women. And it is not about ingratitude toward what may be good intentions from children or relatives. It is about defending the right to decide for oneself and not to lose autonomy.

I have sometimes heard that old age is like a return to childhood, but that analogy, besides being false, is cruel. It assumes that older people lose the ability to decide, to think for themselves, to take (and continue taking) the reins of their own lives —their agency. Thus, the affection and concern of the children can become a heavy burden, partly nullifying their mothers, something accepted as normal, especially if these mothers have lived a life of obedience or dependency, but which causes great suffering. Freedom seems never to arrive, and adulthood is denied to them.

“Well, my son, every time he comes here, he won’t stop nagging me: ‘You really should, Mom, you really should, Mom.’ And I, just to avoid upsetting him further, say, ‘Alright, my son, fine, let’s go, I’ll move out of here.’” This woman told me how she exchanged her small but cozy home for another she did not choose and does not like, where she pays more, has less storage space, and had to get rid of furniture and memories. “Just to please my son.” The son’s intention might have been good; he didn’t like his mother’s old neighborhood. But he didn’t consider whether the one who had to like it —his mother— actually did.

These examples are not anecdotal. They reflect a deep reconfiguration of power relations between generations. The son or daughter who once obeyed now decides. The mother, who once was the adult reference, is now managed by the very person she once cared for and raised. And in the case of many widows, this management is justified in the name of well-being, but in reality, it reproduces old structures of guardianship over women.

Other quotes from many interviews point to the same pattern: the lives of many older widowed women are not the result of their own decisions but of those made by others —their children. Decisions marked by affection, overprotection, but also by a certain distrust in the capacity of the elderly person, and even sometimes by fear of social judgment. Because somehow, a woman alone (and especially an older one) is still seen as a misfit within the dominant gender logic. As if “something were missing.” Something to cling to, something to take care of and protect her, but also to decide for her. In a way, even within the love of sons and daughters, the false idea is reinforced that we are halves waiting for our “other half,” and that, upon losing it, we are forever incomplete.

For some women, widowhood is the first real opportunity to be themselves —to manage their money, their time, their home. Their life. It is the chance to start existing in the first person. But sometimes this possibility —to exercise one’s own agency— depends on the good judgment of sons, daughters, grandchildren, and other relatives who, though full of good intentions, can become jailers —affectionate and well-meaning, but jailers nonetheless.

Widowhood can be a rediscovery of oneself, as long as it does not impose a new form of minority status. But for older widows not to become invisible and lost in the obedience learned over an entire life —an obedience imposed by the system— we need to recognize their capacity for choice, their autonomy, and their right not to have to justify every step.

In a world that still looks at older women with condescension or paternalism, listening to what they have to say before telling them “What’s best for them” is a form of justice. Perhaps this brief reflection will help us understand that good intentions, when they do not consider the person, they are directed to, can become a form of imposed unhappiness. Let us remember that widowhood, besides being a loss, can also mark the beginning of a different way of being in the world and of knowing oneself —a freer, more conscious, and —finally— one’s own way.