"Intergenerational transfers and ageing in Spain, an analysis from 1970 to the present" - Report 2

This project aims to carry out an analysis of the effects of ageing on the economy in Spain. The methodology to be used are the so-called National Transfer Accounts (NTAs). It is a methodology developed since the early 2000s, in an international project led by the American Universities of Berkeley and Hawaii, in which more than sixty countries from all over the world (including Spain) are currently participating. The NTA estimation method has been approved and published in a manual by the United Nations (Population Division).

The NTA Methodology

ATNs consist of estimating, for each moment of time and for a given economy (for the moment the analysis is carried out by countries), all the resource flows that take place between the different age groups of the generations that live together. In strictly economic terms, the life cycle of people can be divided, in general terms, into three main stages that we will call: childhood-early youth, active age and retirement age. During working age, individuals have the capacity to work that allows them to generate the resources necessary to meet their consumption needs, while in childhood and retirement, they lack those resources. Thus, it is essential that there be some kind of mechanism that allows, at all times, intergenerational transfers necessary for children and the elderly to consume and meet their needs. There are basically three intergenerational redistribution mechanisms: families, the public sector and markets.

NTAs provide information on all resource flows between individuals of different ages living together at a given time. However, the procedure for their estimation is complex and requires a significant workload in terms of searching for and processing statistical data at the micro level. NTAs do not only provide profiles of consumption and labour income, but also of all the variables into which they can be broken down, as well as of the different mechanisms for financing the consumption needs of different ages. Thus, profiles of private transfers (both intra and inter-family), public transfers (all taxes, social contributions and all public expenditures) and intertemporal reallocations of assets are constructed. All profiles are obtained per capita and at aggregate level (multiplying each profile by the population in each age group). The aggregates must match those provided by each country's National Accounts, so that the ATNs are consistent with the National Accounts.

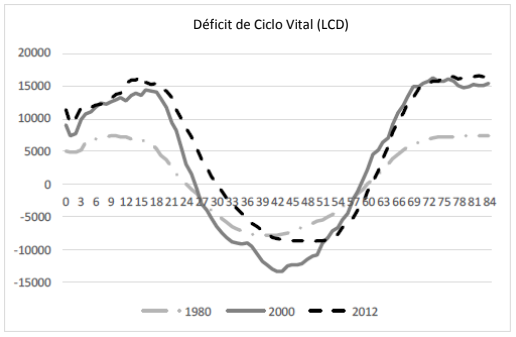

The life cycle deficit (LCD) is defined as the difference, for each age, between labour income and consumption. Irremediably, people have to face a deficit (LCD) during the stages in which they do not have the capacity to generate income from work (childhood and old age), while for a good part of their active life they will generate a surplus (consumption below labour income). The LCD must be financed through the three intergenerational transfer mechanisms mentioned above: family transfers, public transfers or reallocations of assets through the markets themselves. The importance of these three mechanisms is different in each country and has probably undergone significant variations throughout history. The aim of this project is precisely to analyse this temporal evolution by studying the interaction between the three mechanisms of intergenerational income redistribution. The time period contemplated in this analysis goes from 1970 to the present. In this way, it is intended to observe the consolidation of the welfare state in Spain, together with the effects of demographic and educational transitions. Some preliminary results are presented below. To this end, two time stages have been differentiated, conditioned by the availability of data to construct the NTAs in each case (1970-2000 and 2000-2012).

NTA estimates: analysis of available data sources

NTA estimation is an intensive and exhaustive task due to the large amount of data to be worked with. On the one hand, microdata on income and consumption are needed to allow their imputation by age. For Spain, income microdata must be extracted from the Living Conditions Survey (EU-SILC), while those corresponding to consumption come from the Household Budget Survey (HBS). However, the availability of these surveys is limited to the most recent period, and they are not available for making historical estimates.

The first Household Budget Survey in Spain was carried out by the INE in 1958. However, given that its objective was to study the consumption patterns of the average Spanish household, it excluded certain types of households such as those with high incomes or with unemployed heads of household. In 1964, the INE carried out a second Household Budget Survey, this time with no restrictions on the population surveyed and with much more detailed information on family incomes and expenses. The detail of the information was again improved in the Survey carried out for 1973-74. Unfortunately, none of these three FBS contain the information needed to directly apply the NTA methodology. On the one hand, microdata are not available for 1958 and 1964. In the case of 1973-74, although they are available, the microdata are presented at the household level, without giving details about the composition and characteristics of its members, so it is not possible to impute the information by individuals and ages.

Subsequently, in 1980-81 and 1990-91 two new versions of the Household Budget Survey were carried out following the recommendations of the European Economic Community. The microdata from these two surveys are digitalized and ready for use thanks to the work carried out by a team from the Carlos III University of Madrid1. Thus, the first HBS available to apply the NTA methodology is that of 1980-81, which obliges us to look for some other imputation method beyond that date.

Thus, the aim of the project is to estimate the detailed NTAs for those two periods in which the HBS is available and contains all the information necessary to create profiles by age of consumption and income, while estimating resource flows between ages and consumption patterns of public goods. These estimates will then be compared with those available for the period 2000-2012.

Income is broken down into the necessary categories to subsequently study intergenerational transfers. In particular, it is necessary to distinguish between labour income (wages and income from self-employment), housing income (both real and imputed), capital income, income from private transfers (intra and inter-family), and public income (pensions, unemployment benefits, etc.).

In order to identify resource flows between different ages, consumption data are broken down into consumption of education, health and other categories and, for all of them, a distinction is made between public and private. Information on private health consumption is available in the HBS itself, while the public component, as it is not included in the HBS, should be imputed using the information provided by the National Health Survey, which is only carried out from 1987. With regard to education, the HBS contains information on the educational level of each individual, as well as their consumption of education in the reference year. These data are combined with the information provided in the Statistics on Education in Spain, on the number of enrolled persons by educational level, to finally obtain the profiles by age of public consumption of education.

NTA Estimates: Preliminary Results 1980-2012

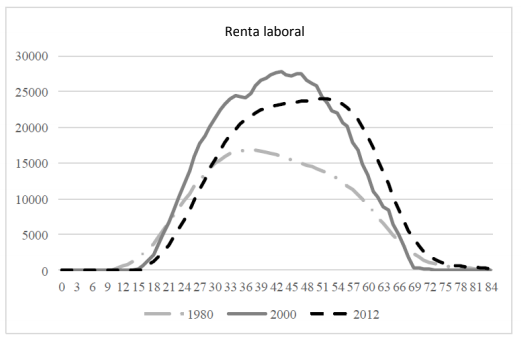

Below are some preliminary results of the 1980-81 estimate of NTAs, and their comparison with the resulting ones for the years 2000 and 2012. First, Figure 1 shows the age profile of labour income per capita, in all cases expressed in Euro 2012. Firstly, between 1980 and 2000 there was a significant increase in per capita labour income, mainly due to the country's favourable economic development during that period (per capita GDP increased by around 78% in those years, according to the calculations of Prados de la Escosura, 2017). The results for 2012 reflect the effects of the serious economic crisis that began in 2008 and particularly affected the economies of Southern Europe, including Spain. According to macroeconomic data, 2012 can be considered one of the worst years of this crisis (the unemployment rate reached a maximum of 26% of the active population). On the one hand, the per capita labour income of young people (under the age of 30) fell below the levels recorded in 1980. The decrease was also notable, but less dramatic, between the ages of 30 and 53, and it was only for those over that age that increases in labour income were recorded in 2012 with respect to 2000.

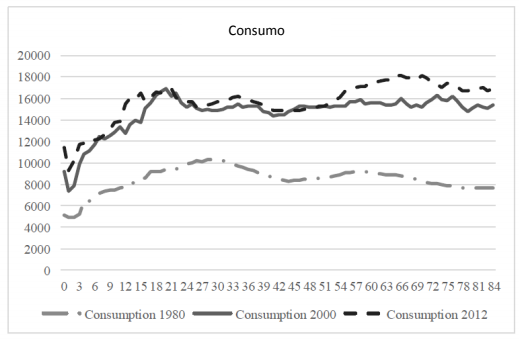

Figure 1. Profile by age of labour income and per capita consumption in Spain in 1980, 2000 and 2012

As far as consumption is concerned, there have also been some significant changes over the last three decades. On the one hand, there was a notable increase in the level of consumption for all ages between 1980 and 2000. Between 2000 and 2012, on the other hand, the increase is much more discrete, and for certain ages even non-existent. On the other hand, it is worth highlighting the change in the shape of the consumption profile by age. In 1980, consumption grew progressively until the age of 30, to suffer a subsequent decline. In 2000, on the other hand, consumption remained practically at the same levels from the age of 22 onwards, while in 2012 there was an increase from the age of 55 onwards. It should be borne in mind that the results for 2012 are conditioned by the strong economic crisis that affected the Spanish economy at that time, which had serious consequences on both production and consumption.

However, as Solé et al. (2012) show, the effects were not homogeneous for all ages. The working-age population suffered serious cuts in labour income as a result of unemployment and falling wages and, as a consequence, also the youngest, who are mainly dependent on family transfers. On the other hand, public pension systems acted as a safety net for the elderly, who were much less affected in their incomes and, therefore, in their consumption.

Life-cycle deficit profile (LCD) in Spain: 1980, 2000 and 2012

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the life cycle deficit age profile (difference between consumption and labour income at each age) in the years observed, determined by the evolution observed in the labour income and consumption profiles. In 1980, the life cycle surplus period took place between the ages of 24 and 60. In 2000, the emergence of surpluses had been delayed to 27 years, and their disappearance had been brought forward to 58. In other words, a total of 4 years less of surplus. While it is true that the level of surplus had increased significantly, it is also true that the same had happened in periods of deficit. For its part, in 2012, the period of surplus does not begin until the age of 31, ending at 59.

The detailed and complete analysis of the NTA obtained for 1980, 1990 and the most current periods (2000 onwards), will allow us to understand many socio-economic changes that have taken place in Spain during the last decades. The change in consumption profiles, labour income and, consequently, life cycle deficit, is the reflection of numerous factors that have influenced the organisation of intergenerational transfers during the same period. On the one hand, the strong educational transition, with a notable increase in schooling rates at all ages, and especially in that of young people from 14-16 years, which has significantly delayed their entry into the labour market. On the other hand, the consolidation of the welfare state and its different spending programmes, especially aimed at the elderly through the pension system and universal health care.

Next objectives

Review and verification of the results obtained for the 1980 NTAs

1990 NTA Estimate

Detailed analysis of the results in coordination with the rest of the subprojects.

1 http://www.eco.uc3m.es/investigacion/epf.html The same work team also digitalized the Household Budget Survey of 1973-74.

1 http://www.eco.uc3m.es/investigacion/epf.html. The same team also digitized the 1973-74 Family Budget Survey.

Main bibliographical references

Bloom, D. E. and D. Canning (2003). "How Demographic Change Can Bolster Economic Performance in Developing Countries", World Economics 4(4): 1-13.

Bloom, D.E. and J.G. Williamson (1998). “Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia”, The World Bank Economic Review, 12(3), 340-375.

Crespo-Cuaresma, J., W. Lutz and W. C. Sanderson (2014). “Is the Demographic Dividend an Education Dividend?” Demography, 51, 299-315.

Cutler, D., J. Poterba, L. Sheiner and L. Summers (1990). “An Ageing Society: Opportunity or Challenge”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 1-74.

Kelley, A. C. and R. M. Schmidt (2005). “Saving Dependency and Development”, Journal of Population Economics, 9 (4), 365-386.

Lee, R. and A. Mason (2011). Population Ageing and the Generational Economy. A Global Perspective. Edward Elgar, USA.

Lee, R., A. Mason and T. Miller (2000). “Life Cycle Saving and the Demographic Transition: The Case of Taiwan”. Population and Development Review, 26, 194-219.

Lee, R., A. Mason and T. Miller (2003). “Saving, Wealth and the Transition from Transfers to Individual Responsibility: The cases of Taiwan and the United States”. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 105, 339-357.

Mason, A. (2005). Demographic Transition and Demographic Dividends in Developed and Developing Countries, United Nations Expert Group meeting on Social and Economic Implications of Changing Population Age Structure, Mexico, UN/POP/PD/2005/2.

Mason, A. and R. Lee (2006). "Reform and Support Systems for the Elderly in Developing Countries: Capturing the Second Demographic Dividend". GENUS LXII(2), 11-35

Patxot, C., E. Rentería, M. Sánchez-Romero and G. Souto (2011). “How intergenerational transfers finance the lifecycle deficit in Spain”, in R. Lee and A. Mason, Population Aging and the Generational Economy. A Global Perspective, Edward Elgar, p.241-255.

Patxot, C., E. Rentería, M. Sánchez-Romero and G. Souto (2012). “Measuring the balance of government intervention on forward and backward family transfers using NTA estimates: the modified Lee arrows”, International Tax and Public Finance, 19, p. 442-461.

Patxot, C., E. Rentería and G. Souto (2015). “Can we keep the pre-crisis living standards? An analysis based on NTA profiles in Spain”, Journal of Economics of Ageing, 5, pp. 54-62.

Prados de la Escosura, L. (2017). Spanish Economic Growth 1850-2015. London, Palgrave MacMillan.

Prskawetz, A. and J. Sambt (2014). “Economic support ratios and the demographic dividend in Europe”, Demographic Research, 30 (34), 963-1010.

Rentería, E., G. Souto, I. Mejía-Guevara and C. Patxot (2016). “The effects of education on the demographic dividend”, Population and Development Review, 42 (4), p. 651-671.

Sánchez-Romero, M., G. Abio, C. Patxot, G. Souto (2018). “Contribution of Demography to Economic Growth”, SERIEs Journal 9, pp. 29-64.

Solé, M., G. Souto, G. Papadomichelakis, E. Rentería y C. Patxot (2019). "Protecting the elderly and children in times of crisis: An Analysis based on National Transfer Accounts", Journal of Economics of Ageing (forthcoming).

United Nations (UN) (2013). National Transfer Accounts Manual. Measuring and Analysing the Generational Economy. Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations Publication, New York.